The Interborough Express Study

The Interborough Express Study

In April, Governor Hochul unveiled her major transit infrastructure investments for fiscal year 2025. Among these projects, $52 million has been dedicated to the design and engineering of the Interborough Express, a new light-rail line set to link Brooklyn and Queens. IBX is expected to significantly improve transit access in Brooklyn and Queens, which have long been underserved by public transportation. Its greatest impact will be felt by the residents along the corridor, a majority of whom are low-income, transit-dependent, and from communities of color, thereby enhancing connectivity and promoting equity.

As we expand our research beyond the cost drivers of transit projects, we have decided to study IBX’s development potential, by promoting strategic land-use changes and street redesigns that we consider necessary to maximize the $5.5 billion investment that will be made to build the line. Even though IBX will increase job access for the residents living close to the proposed stations, the corridor is severely low density, underbuilt and predominantly residential. Moreover, many areas along the corridor are not walking-friendly, with wide arterial roads and inadequate pedestrian infrastructure. With our research, we seek to answer the questions of where the city should upzone, build more housing, encourage mixed-use development and carry out street redesigns. These changes would promote greater ridership on the line, reduce commute times, and ultimately expand transit-friendly areas in Queens and Brooklyn, reaching further east and south.

What is the IBX?

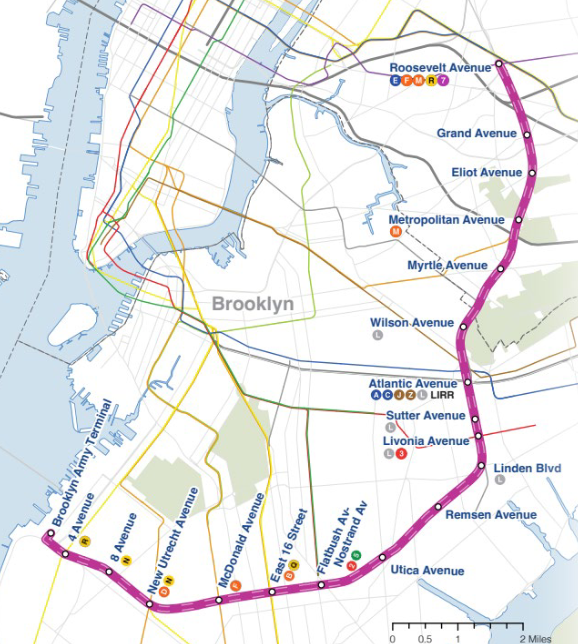

The Interborough Express is a proposed rapid transit project that will use an existing, 14-mile freight right-of-way in New York City. The line will run along the Bay Ridge Branch owned by MTA LIRR (southern 11 miles) and the Fremont Secondary owned by CSX (northern 3 miles), extending from Bay Ridge in Brooklyn to Jackson Heights in Queens.

A total of 19 stations have been proposed along the line that would provide transfers to 17 subway lines as well as the LIRR. The MTA predicts that the IBX will attract 115,000 daily weekday ridership and cost $5.5 billion. There are 900,000 New Yorkers and 260,000 jobs within a 0.5 mile of the corridor. The project is currently working its way through the engineering and environmental permitting process. To access the MTA resources and track progress on the project, go to this link.

The proposed Interborough Express Line. Source: https://new.mta.info/document/87606

Our Analyses

Our goal in sharing research incrementally and informally is to actively engage with the transportation community. We seek to discuss not only our findings and results but also the various data, methods, and tools we employ. It is our intention to share our data and code, as soon as we have time to clean and organize them according to sharable standards.

Below is a summary of the content we plan to share through these articles and some images to provide a sneak-peek into our upcoming articles.

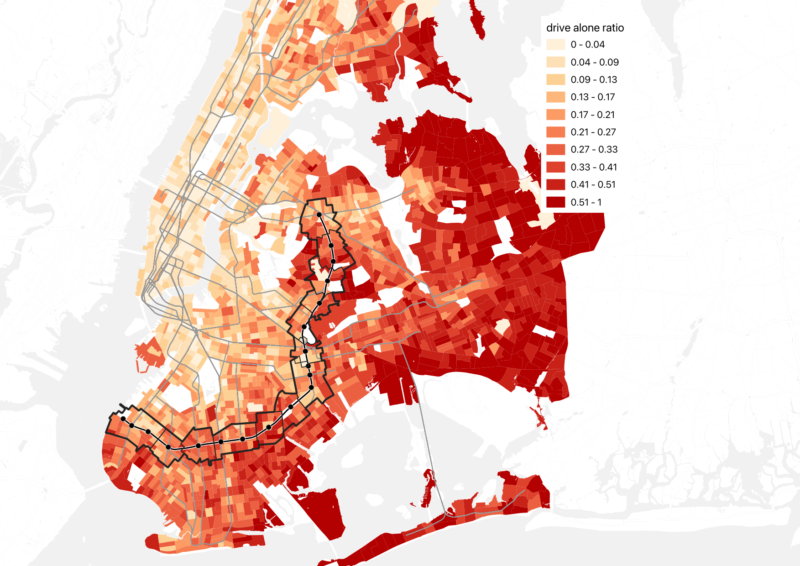

- The existing conditions regarding the demographics, availability of and access to jobs, street-network connectivity and travel behavior of current residents along the corridor. We use census data, tax lot data and the street network topology for these analyses and present them through choropleth mapping and accessible data visualization. The maps give a sense of how residential and commercial uses are distributed in the vicinity of the proposed stations, how population and job densities change across these areas, and the different building typologies and preferred commuting modes of the residents living along the corridor.

Travel behavior: Motor vehicle use along the IBX

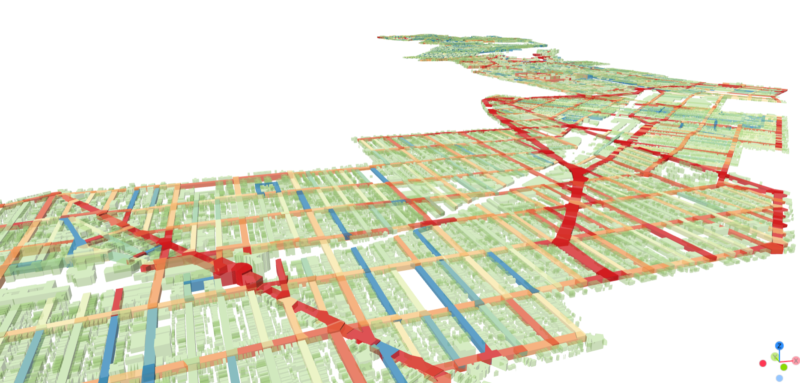

- A street-level study of the corridor, utilizing a 3-dimensional, morphological analysis method named Convex and Solid Voids. This method was developed at the University of Lisbon and both Joao Paulouro and myself have been involved in its development. I have utilized this method to measure walkability attributes in urban neighborhoods in my dissertation, which has informed part of the analysis we performed on the IBX. As walkability is an important criteria when assessing a transit corridor’s TOD potential, we decided to implement this street-level analysis to measure walkability-related attributes. One of our intentions was also to further improve the method itself.

- As part of the Convex and Solid-Void analysis study, we developed a workflow that identified boundary properties of each tax lot using Google Street View and planimetric data. We utilized image processing and ML algorithms to estimate whether a tax lot’s boundary existed, its height and visual characteristics. We used the results as input to calculate what we termed ‘cognitive height’. This is an important measure of Convex and Solid-Voids that represents the perceived height of a street’s volumetric surroundings, that is to say, the perceived heights of buildings and their immediate boundaries.

Convex and Solid-Void Analysis: 3d interface showing the IBX corridor’s Flatbush Avenue Station and stations to its north

- We are working on estimating the ridership for the proposed IBX stations using two different methods simultaneously. Both methods have been utilized as alternatives to the traditional four-step model for predicting ridership for new transit lines. We are testing the STOPS software developed by the FTA, by feeding it our own data with the goal of comparing results to MTA’s initially stated 115,000 daily weekday riders. We are also developing our own ML algorithm based on census, tax lot, GTFS and network analysis data. We will share the results as well as the workflows for both methods, and anticipate discussing these comparatively.

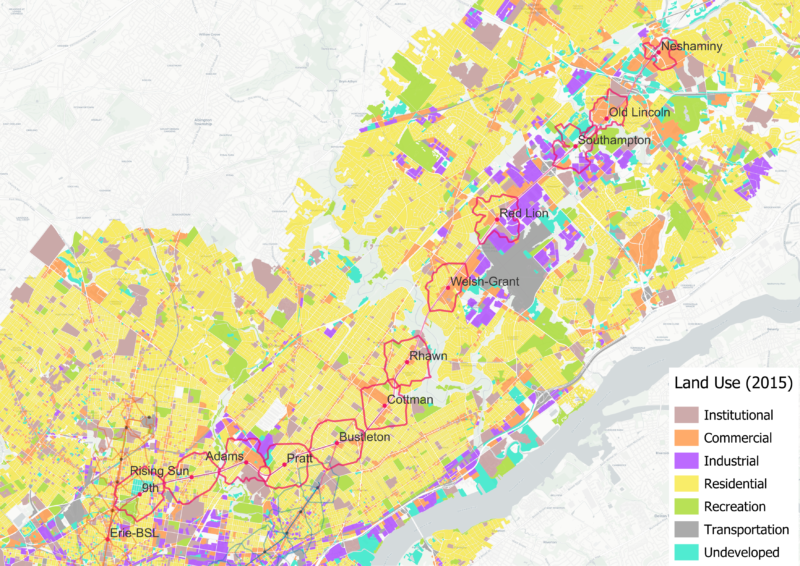

- While working on the IBX, we cultivated an interest in the Roosevelt Boulevard Subway, a proposed high-speed rail line along a heavily trafficked artery in Philadelphia. Since most of our analyses are based on open data incorporated into a semi-automated workflow, we decided to implement them on the RBS and come up with TOD-oriented recommendations for the RBS corridor.

Land use along the Roosevelt Boulevard Subway

We have also shared current conditions analysis of the RBS with a group of agency officials, advocates, journalists and NGO leaders in Philadelphia. The consensus among them was that ridership estimates will be the most important determinant to evaluate the feasibility of investment to build the RBS. In upcoming articles, we will discuss our predictions consecutively for the IBX and the RBS.

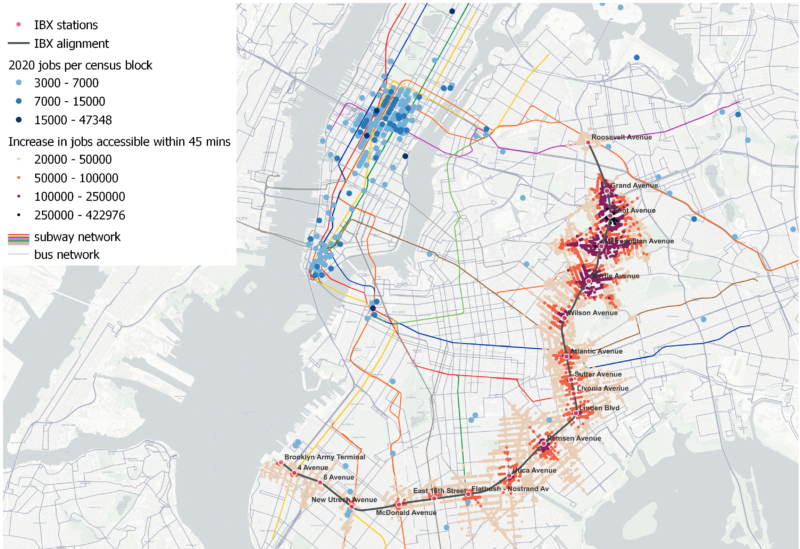

- Locations and accessibility of jobs to residents through different modes of transportation as well as the potential impact of a new transit system on this, serve as important indicators for assessing the feasibility of investing in the system. To evaluate this, we utilized some existing transit modeling and network analyses tools, and identified geographies within and outside of the proposed transit corridors that will see the most significant changes in job accessibility. An article will focus on these findings.

Access to jobs by transit.

To stay updated on our interim findings, please follow our work on this page. Our final article will unveil our comprehensive report, complete with links to exclusive datasets, charts, maps, along with the measures, algorithms and code we’ve developed.